His

History

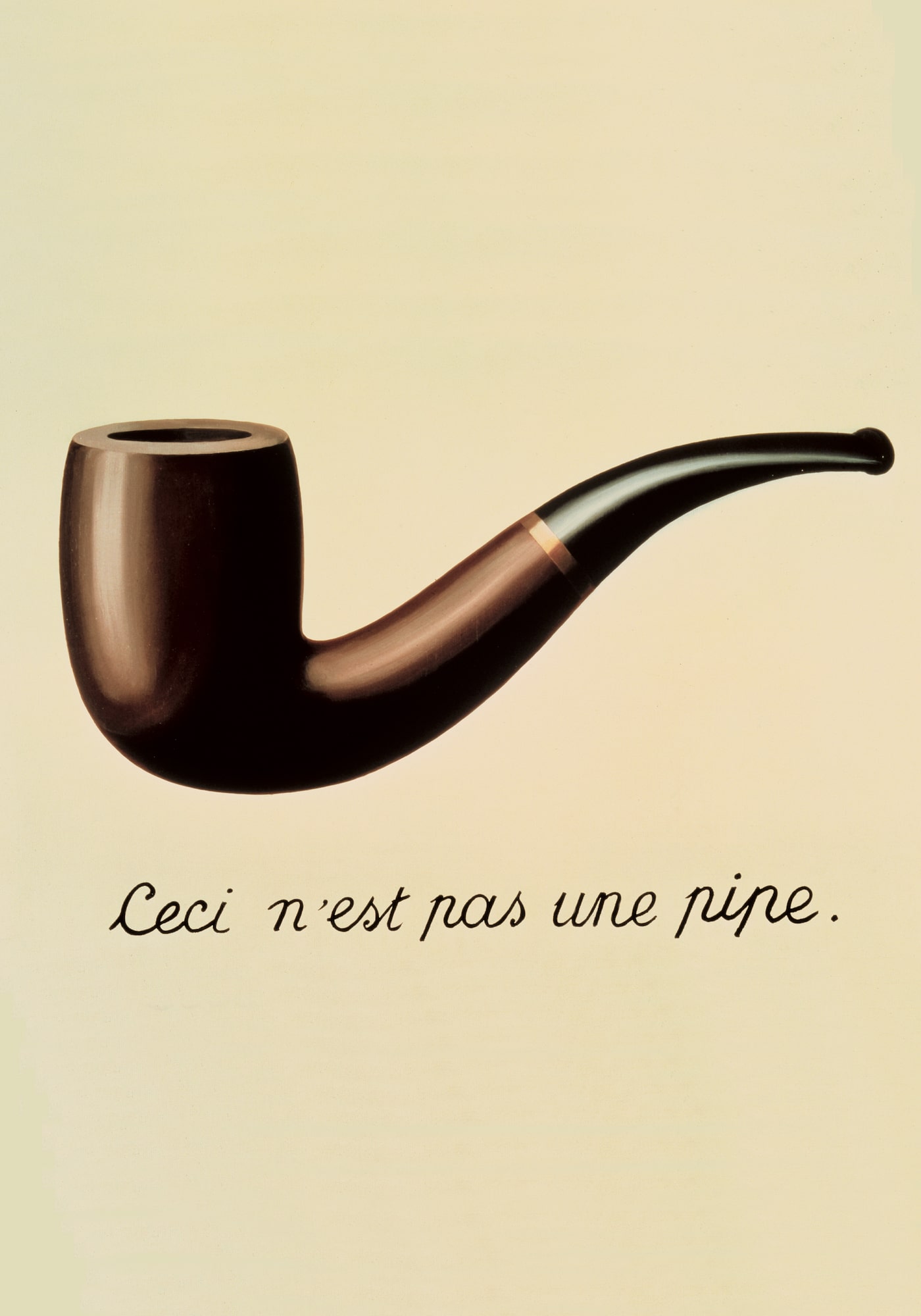

René Magritte

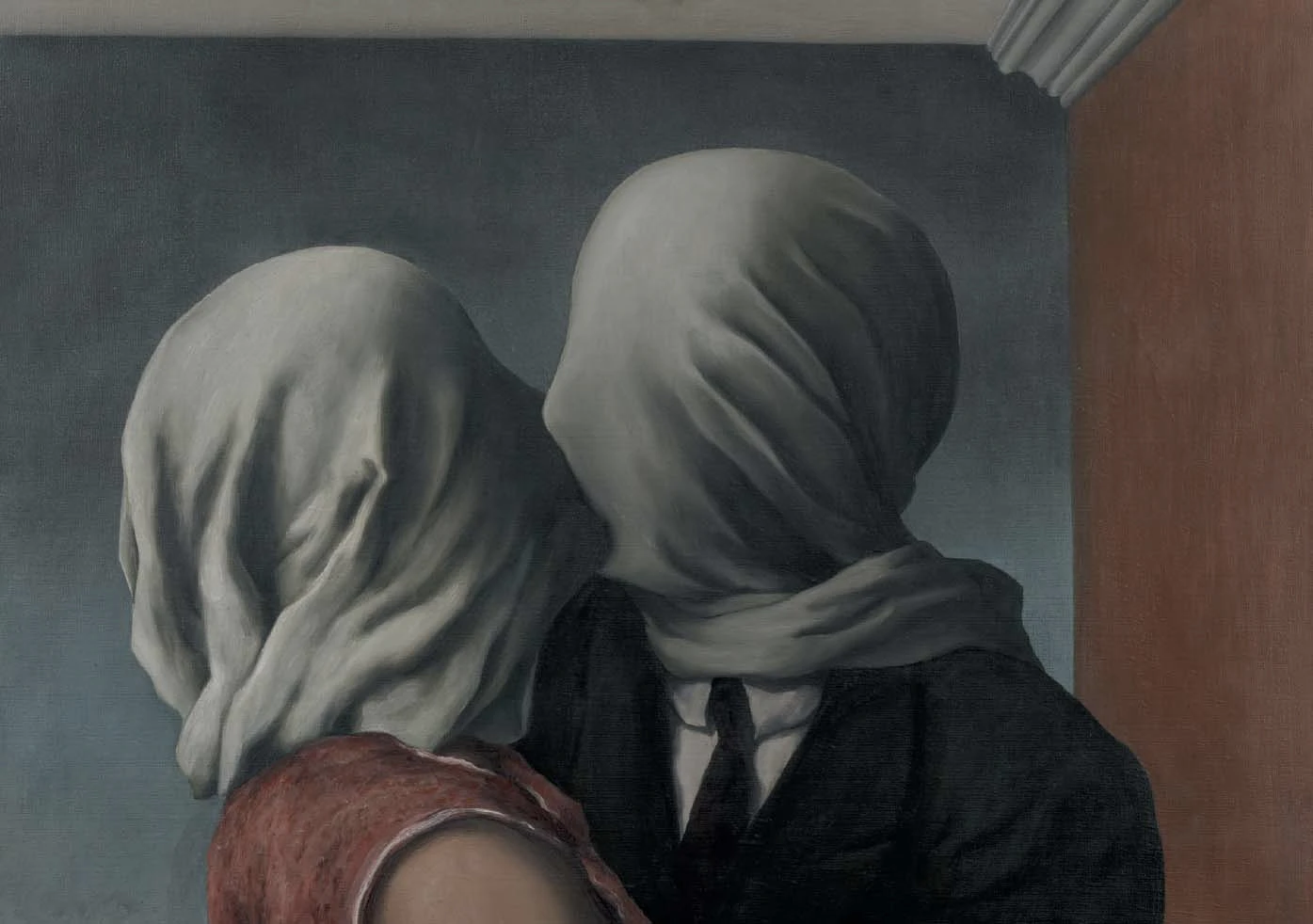

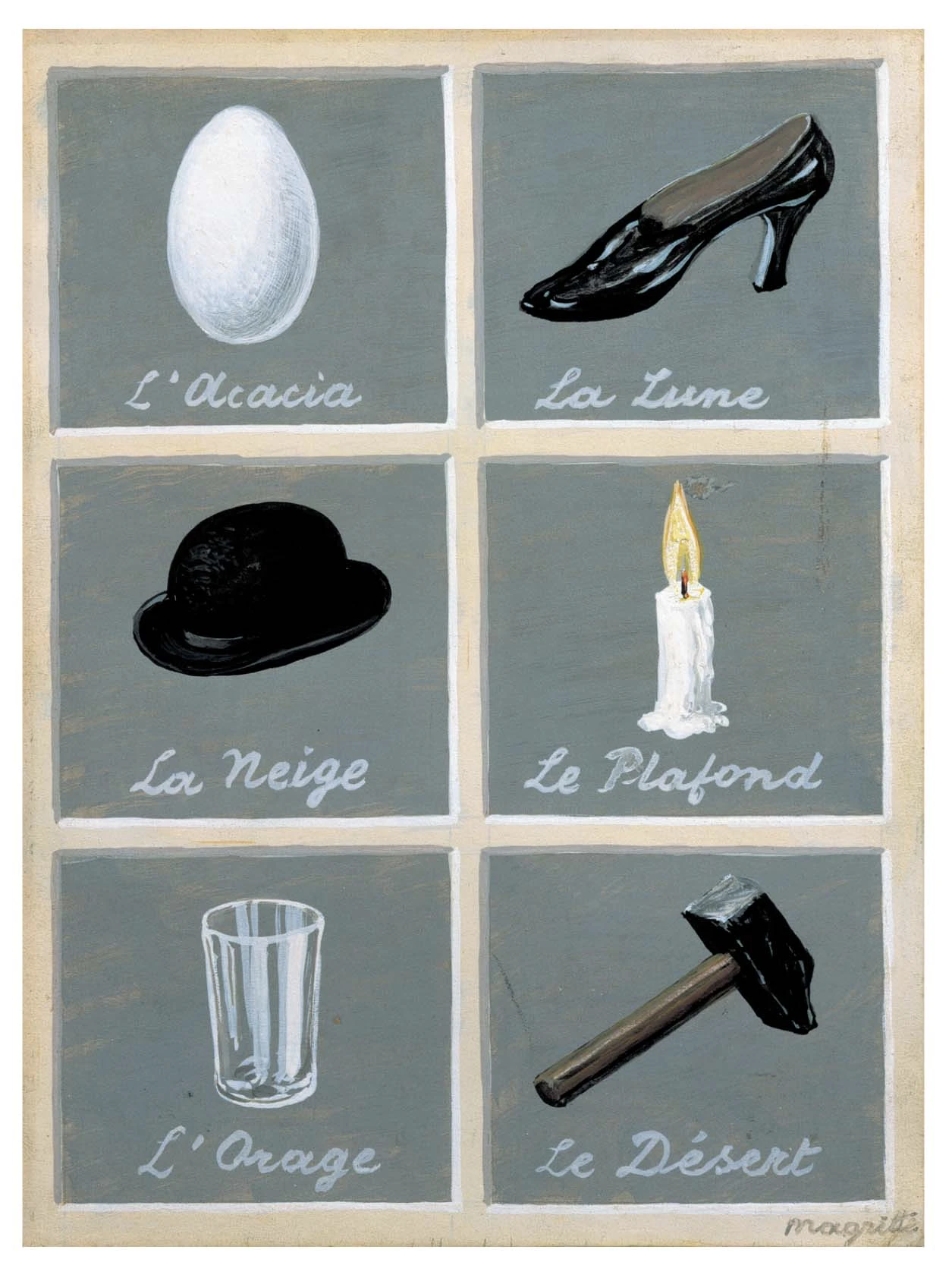

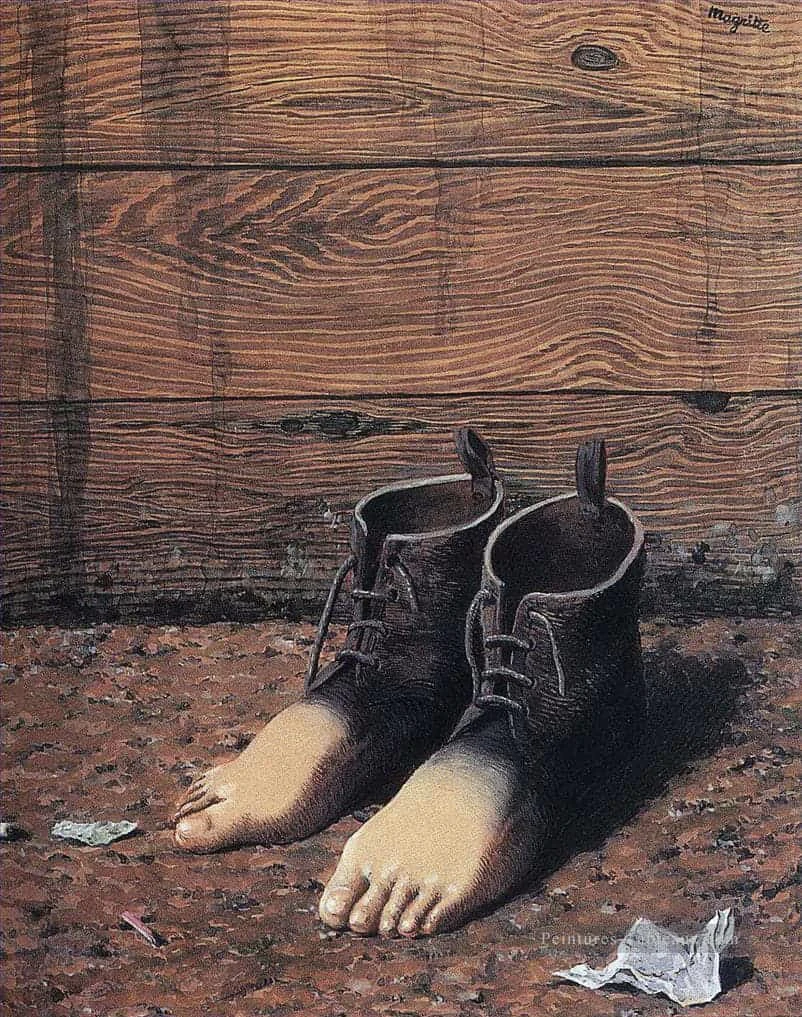

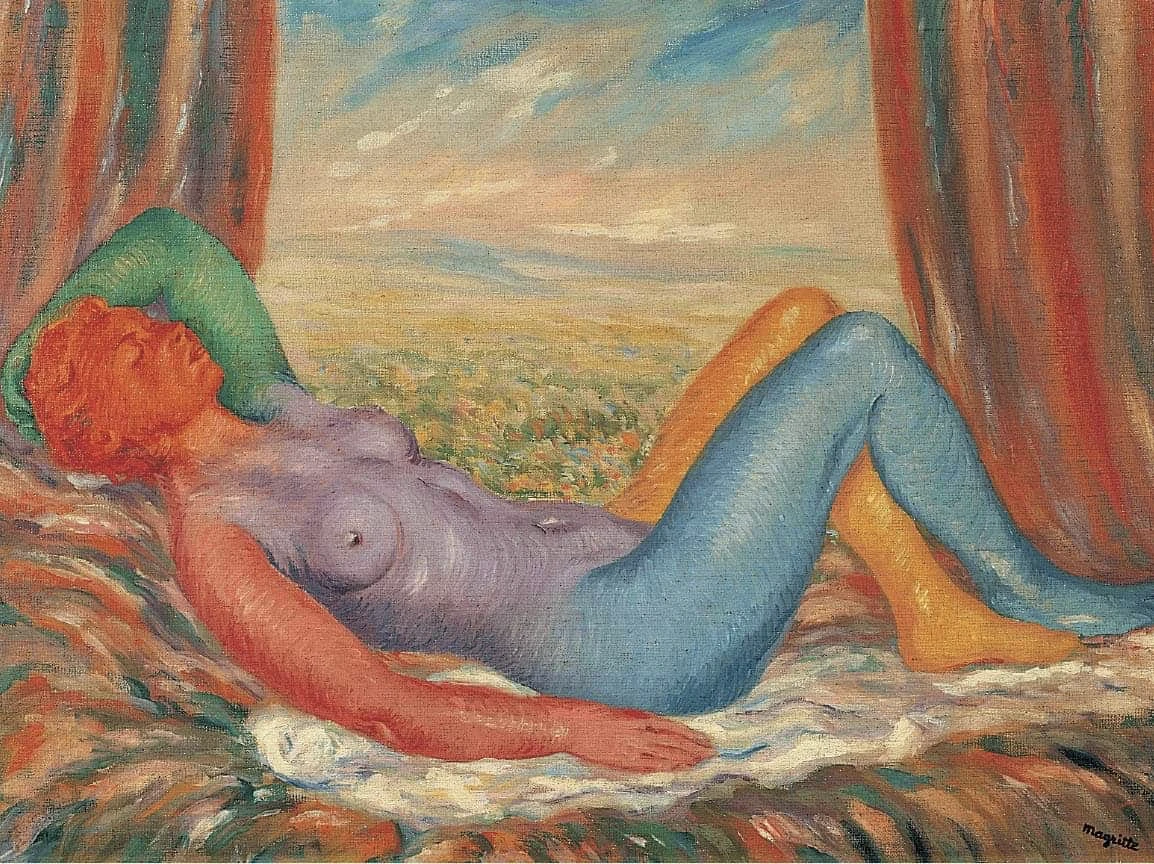

René Magritte’s body of work has become part of our collective unconsciousness. His gaze-arresting images continue to go around the world and captivate the imagination of young and old alike. His secret? As the master of Mystery, Magritte manages to turn our perceptions on their head with seeming simplicity. In fact, he thoroughly throws the world in which we live into disarray. In his canvases, items as commonplace as an apple, a glass of water, an umbrella or a bowler hat, suddenly become refreshingly quirky! Magritte teaches us how to see the world around us in a different light.

SURREALISM

His

Work

LA TRAHISON DES IMAGES (THE TREACHERY OF IMAGES)

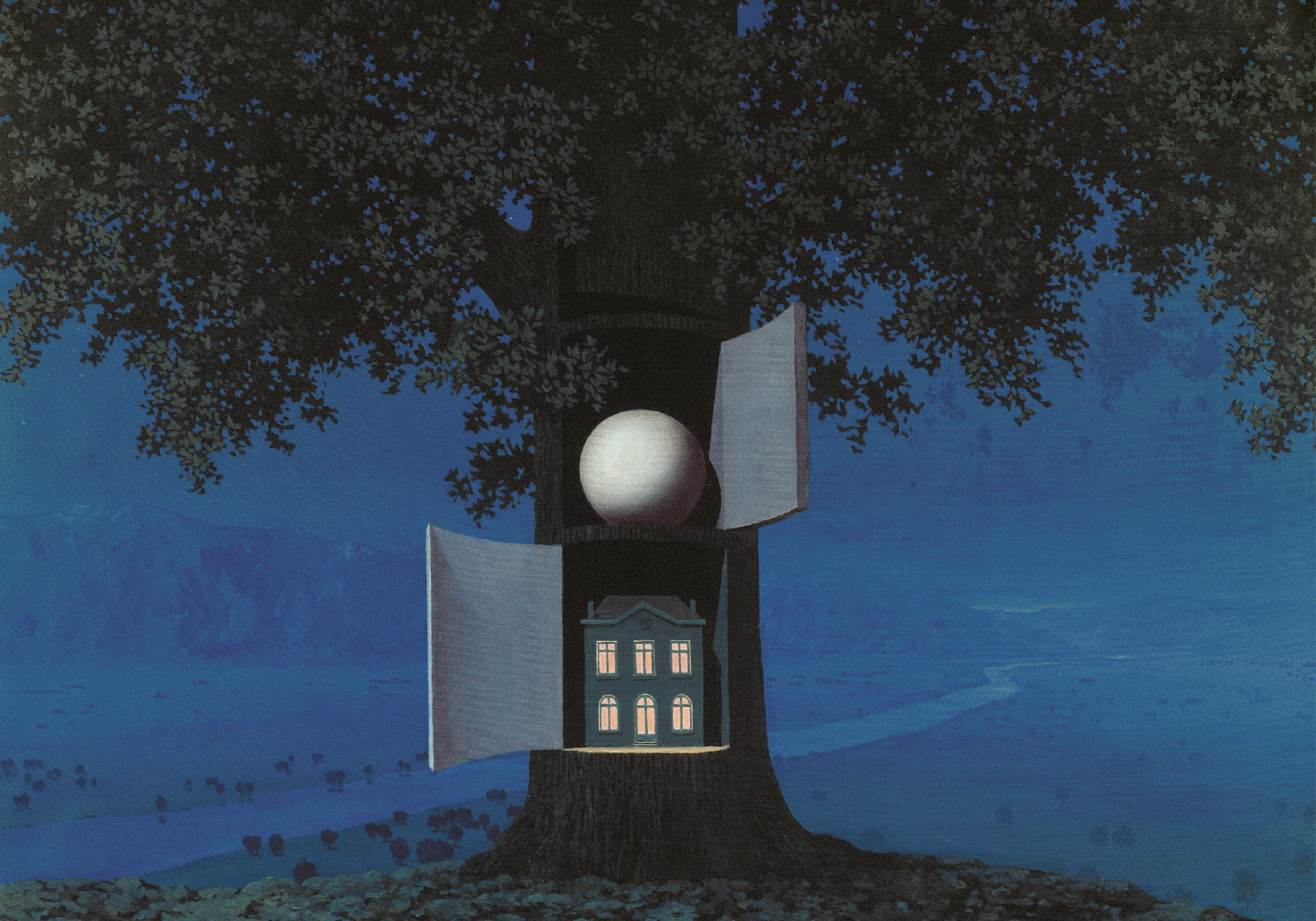

L'EMPIRE DES LUMIÈRES (THE EMPIRE OF LIGHT)

LE FILS DE L'HOMME (THE SON OF MAN)

Receive surreal news by email

You may unsubscribe at any moment. For that purpose, please find our contact info in the legal notice.